The Climate Brides Podcast

The Climate Brides Podcast

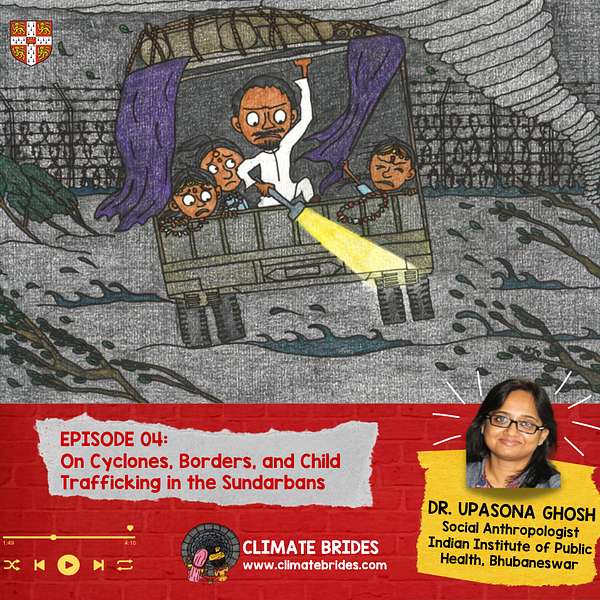

Episode 04: Upasona Ghosh on cyclones, borders, and child trafficking in the Sundarbans

Reetika: Welcome to the Climate Brides podcast, where we try to untie the knots between climate change and child marriage. My name is Reetika Revathy Subramanian, and I am your host. Join me as I speak with survivors, frontline workers, activists, journalists, and researchers in and from South Asia, to unpack the everyday lives and resistances of young communities braving some of the biggest challenges of the 21st century. Subscribe now wherever you get your podcasts.

The Climate Brides podcast is supported by the University of Cambridge Public Engagement Starter Fund 2021. If you want to learn more about today’s topic, head over to our website, where we will have full transcripts of the episode, a specially curated reading list, climate models and infographics. Until then, follow the Climate Brides page on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to stay tuned, and stay updated.

Reetika: The world’s largest mangrove rainforest, the Sundarbans, sprawls across India and Bangladesh and forms a natural border between the Bengal delta and the Indian Ocean. With worsening cyclones, sea level rise, and loss of land to erosion and salt water, the forested islands of the Sundarbans are considered to be one of the most climate vulnerable locations on the planet. These disasters have repeatedly uprooted families and decimated the incomes of residents who have traditionally relied heavily on agriculture and fishing for their livelihoods. Multiple UN agencies such as the UNICEF and UN Development Programme have warned that climate change will increase exploitation of minors including child trafficking and marriage. This fear is already a reality in the Sundarbans. In today’s episode, we are joined by Dr Upasona Ghosh, a senior social anthropologist working in the fields of public health, gender and climate change. She is currently affiliated with the Indian Institute of Public Health, Bhubaneswar in India. Through her work, which is primarily situated in the Sundarbans, Dr Ghosh studies social vulnerabilities and political-economic dynamics of communities braving climate change at the last-mile. Dr Ghosh has been published in several leading journals including Lancet Planetary Health, BMJ Asia and British Medical Journal. We are very excited to learn from her experiences and insights.

Reetika: Hello. Thank you so much for joining us today and I'm really excited to welcome you to the Climate Brides Podcast.

Upasona: Thank you so much for inviting me in this exciting thing.

Reetika: So, to begin with, it will be great to know a little bit more about the work that you do, and if you can give us an overview of the kind of work that you've been doing over the years.

Upasona: OK. So, to begin with my work, I'm basically I'm an anthropologist working in the juncture of public health, climate change and gender. So, my focus areas are how climate change is playing an important role in shaping out people's life, their livelihood, their identity and the social challenges they are facing. So, I get the opportunity to work in such a climatically vulnerable zone, which is called the Sundarbans, which is divided between India and Bangladesh. It is the largest mangrove delta and I have done my PhD on climate change and social determinants of people's health and their well-being in that particular region and close to 10 years I'm researching in Sundarbans. I mean in front of my eyes I have seen the society is changing. As climate change is impacting their livelihood, their life, and in fact, every sphere of their life. So, it's very unfortunate to see this, but at the same time, it is fascinating to see people's aspirations especially of the girls and the women and how they are trying to rebuild the entire system towards the climate change transformations

Reetika: OK, great. Thank you so much. And you know, this brings me to the question around like the particular vulnerabilities of the Sundarbans, you know, where you have spent so much time. Could you tell us a bit more on the climate vulnerabilities of the region?

Upasona: OK, so climate change basically, the Sunderbans is the largest mangrove delta in the world, it is a world heritage site, a UNESCO heritage site. Though ecologically the region is unified, but it has been divided politically between India and Bangladesh. So both the countries have their own political way of handling this region, which has a colonial history of people inhabiting there. They have a jungle-based economy. But now, close to 30-40 years, mainly the traditional livelihood like the agriculture and fishing are depleting because of sea level rise, because of salinity intrusion in the agricultural field, and Sweetwater fishing ponds, as well as, there are cyclones almost every year. But as we know at the same time, the cascading effect of this direct impact or the immediate impact like cyclone or floods, Sundarbans has its long term impact of climate change like food security in terms of their shelter and in terms of their societal transitions. As the livelihood is depleting there, the menfolk especially, the men folks are migrating outside as wage laborers. And the women are basically the main inhabitants now in the Sundarbans. So, the women are now facing a kind of, you know, triple burden of work. So, first thing they have to take care of their children. They have to take care of their elderly in-laws. They have to take part in the livelihood restoration processes which they have lost during the floods and cyclones as well as they have to do all the household chores. So, basically the women are facing this kind of burdens, and which has which has a kind of, you know, twisted gender negotiation. So, basically, if we see the ecological impacts, definitely it has the impact on the livelihood, which is very crucial and the cascading impacts on the social life.

Reetika: Right. And you know, in that context, could you tell us a bit more on the local populations themselves like, you know, could you tell us a bit more on the demography of the populations, like in terms of, yeah, the people living there?

Upasona: OK, so, if we see the demography of Sundarbans, the majority part, the 70% of Sundarbans, is in Bangladesh. India got the rest of the 30%. So, in this 30% in Sundarbans, we have close to five million people, and in the Bangladesh part, most of it is the reserve forest. The Royal Bengal Tigers are famous from Sundarbans. So, most of the reserve forest area are now in Bangladesh. And there also we have found around 2.5 million people. So, these people basically, religiously they are Hindus and Muslims in both the countries. The interesting thing of their cultural syncretism that is called the cult of Bonbibi. So, Bonbibi is the deity of the jungle. When you are going to the jungle to collect forest products like the honey, paraffin, then, any other jungle wood, the Bonbibi is the goddess who can protect you from the tiger attack or the crocodile attack. So, but that was that was, you know, kind of a glue that binded the two religious peoples together since their inhabitation. But very recently as the climate change impacts are affecting the livelihood and people, and I mean the forest rules of both the countries, people are no more you know able to go to the jungle in that frequency that they were previously. So, their jungle dependency is, uh, receding and so is their dependency or belief on Bonbibi. So, here and the mainstream religions like Hinduism and Islam are taking place of that cultural, culturally syncretic, you know, cult of Bonbibi. And in the Indian part, most of the so-called schedule caste and schedule tribe populations, the marginalised populations in terms of Indian constitution, their inhabitations are there. So, socially, culturally and economically, the Sundarban peoples, both in India and Bangladesh, they are historically marginalised and climate change is just pushing them towards more marginalisation.

Reetika: Right. And, you know, one of the things that the region has been known about as you also mentioned earlier has been, you know, these intense and frequent cyclones in particular. You know, one talks about climate change and in the last 10 years or so, the intensity that we've seen globally has also increased. Can you speak a bit more on what has the region seen say in the last decade, you know, what are some of the big sort of events?

Upasona: OK. The first big event was Cyclone Aila that happened in 2009, both in India and Bangladesh part of Sundarbans, which had a landfall near the Sundarbans. So after that it was a turning point, which I would like to mention here that since then, especially the Indian part of Sundarbans have started getting the developmental searchlights. For example, soon after Aila there were lots of, you know, developmental agencies, aid organizations, and they came for the rehabilitation, for the rescue and the distributions of goods, resources, everything. If we see in the socio-economic pattern of Sundarbans, it was a very crucial event, the Aila in 2009. And after that, in the Sundarbans, you know, resource politics has changed quite a lot. So, but the impact of the work on climate change impacts or the interventions specifically towards, you know, adopting to climate change was very less. At the same time, in the Bangladesh part, as it has faced more cyclones than the Indian part, it has developed its disaster risk reduction plan, climate adaptation plan much before the Indian part. So, in May 2020, another big event happened to the Indian part of Sundarbans that is the Cyclone Amphan. I can say that this event gave a big push to the policy change in terms of Sundarbans. But before the government could plan, or even the people got out of the shock of Amphan, Cyclone Yaas happened in 2021. So, this two big cyclones, back-to-back, really broke the backbone, the economy, and the policy backbone of the Sundarbans.

Reetika: Right. No, right. Since you've spent considerable amount of time on the field as well, what are some of the ways in which like the local communities in the Sundarbans understand climate change. I mean, is it referred to as climate change problem, or, you know, in terms of daily experiences and events, which sort of make up the imagination of it?

Upasona: OK, this is a very interesting question. You know, if you talk to any person in a region like Sundarbans, you can imagine that they don't have the scientific knowledge of climate change. But interestingly, some top-down knowledge, and I would not say it is knowledge, but it is a top-down blame-game that is happening towards the people of Sundarbans. As though they have done something wrong, they have cut the mangroves, and that's why this cyclones are happening. So, this is a very dominant narrative of climate change, which has been imposed to the people of Sundarbans and they really feel that. They definitely perceive the weather changes, the sea-level rise; they can identify from their childhood knowledge or from their childhood experience that definitely the sea-level is rising and the river is getting shallower. So, that's their understanding. They can also figure out that you know the rainfall is very unpredictable now and they can also understand that the heat has increased, the cyclonic events have increased. So, they have these kind of knowledges from their experience. These are experiential knowledge of the Sundarbans peoples. But at the same time, as I mentioned earlier, that you know, a very top-down knowledge that you guys have done wrong and that you have to pay for that. So, that is something very dominating there and you can find 2-3 people in every you know village, many journalists, even international journalists, who have interviewed them and they were saying, “Oh my God, this is climate change and we are responsible for that. Now, the God is giving it back to us, blah blah blah.” So, I can't say this is the knowledge of climate change. This is a dominant narrative imposed to them by the policymakers, by the scientist or whoever on the above. You know, in our research, we categorized the heuristics of above, middle, below of the stakeholders or the actors. So, the above are so-called natural scientist, or the policymakers or the administrators, middles are basically the NGOs, or researchers like us, who are trying to breach these different knowledge frames. And the below are the communities. So, every set of actors have their own knowledge frame about climate change.

Reetika: Right. Yeah. You know Dr Ghosh, you mentioned something important about like, you know, communities being busy with just surviving every day. In that sense, one of the aspects that we've seen in a lot climate hotspots has been about the impacts that, you know, this need for survival has on the lives of young women and girls, which is also the focus of the podcast. So, I was wondering if you could talk a bit more on the community of women and girls in the region. And, you know, their specific vulnerabilities.

Upasona: OK, so as I mentioned earlier that to restore the livelihood or to you know just for the subsistence, the menfolk of Sundarbans villages are, you know, out-migrated. So though most of the migration is seasonal migration, not the permanent one, right now in Bangladesh part, most of them have migrated permanently and they end up in Dhaka's slum. But in the Indian part of Sundarbans, they have started this migration seasonally and the women and girls along with the elderly are the ones who are residing in the islands right now. So, they have to face, the women and girls, they have a typical kind of, you know, vicious cycle of vulnerability. So, they have to take care of everything. They have to take care of the children. They have to take care of the households, they have to earn. So, previously, the women who were not part of the economic process of the region, now they are in the party. If you see the economic demography of the region, you will find that many of the women folks join the unskilled labour force. Because as they were the traditional fisherwomen and agriculturists, the farmers, they don't have any other skills, I mean any other alternatives. So, they are not good at you know doing embroidery or something, some cottage industries. So, they were not skilled to that and there is no scope for building their skills on that also. So, the women are ending up, you know, doing jobs of wage labour or agriculture. But at the same time, due to the patriarchal norms and regulations, they are not able to go out with their husbands or brothers or fathers for a better remittance. They have to stick within this island. And they have to find work there. So, their situation is very strenuous. Most of the women are now joining a very risky livelihood options, which is the crab catching. So the crab catching you have to first of all, you have to go to the reserve forest area mostly illegally because there are forest rules, uh, you cannot get into the reserve forest area. You have to take lots of permissions. So, most of them have to stand whole day in the in the, you know, waist deep water to get the crabs, and they are very prone to, you know, the attack of tigers and crocodiles. So, this situation is quite stressful for them, for their health, for their well-being and at the same time for their mental health. Most of the households are facing this livelihood stress, which is increasing the phenomena of domestic violence. So, child marriage, adolescent marriage is rampant. I mean, you can find, uh, 14 year-old, 13 year-old, 15 year-old girls getting married, though the official age is 18. But below 18 marriage is very very common. Now another layer is there that it is the region since from the very beginning, these are the international borders regions, and human trafficking in both the countries are very high from this region. There are some NGOs who have the data, like every time the floods happen, the number of girls from Sundarbans has increased in Kolkata's brothels. So they are subjected to human trafficking, prostitution, everything. So, it is a very complex situations and the childline, the government all are doing to you know intervene in this particular area to stop this child marriage, to stop human trafficking. But still now it is there, I mean nothing is working as expected.

Reetika: Yeah, you know, you've covered a range of very, very crucial points and you know which I also wanted to unpack a little more. One of the things that you spoke about was in the context of child marriage. And I wanted to understand one thing in terms of how is a child, like, who's a child, you know, locally, like, I mean, what are the perceptions of who's a child or who's an adult, like, in terms of who's considered to be marriageable in that sense? Are there any community perceptions or is it largely survival-driven?

Upasona: See, in like many parts of India, a girl, as soon as she, gets her menstruation, is marriageable. So, this perceptions are still prevalent in rural India. So, that is the first thing. The literacy rate in Sundarbans, including the female literacy rate, is higher than the state average. So, the typical, you know, stereotypical indicator for a development like the women empowerment indicators as women literacy, that indicator is not working in the Sundarbans. Though the girls are educated, but this survival twist you mentioned rightly, that survival twist is basically pushing them to get married off. So, maybe, if there is no economic stress, maybe that girl could have completed 18 years because there are some government schemes also wherein if you complete your education until 18 years, you will get some money from the government. So, there are some schemes and which is running well in other parts of West Bengal. But in case of Sundarbans, the major pushes now the, you know, reducing numbers from the family. And many a times the parents know that this marriage may end up in a, you know, kind of trafficking. But still they want to, you know, get rid off an extra head from the family. So, that is that is the complex situation.

Reetika: Right. And you know, like you point out, there are so many layers involved. One of the things that I want to ask you a bit more on was, you know, how are these marriages actually fixed? What are the exchanges involved from your conversations on the ground? What are some of the marriage practices that are involved? Like, for instance, we were recently talking to somebody who works on the IDP camps in Afghanistan and there's this whole practice of bride price that exists, you know, which is negotiated with drought and, you know, which has an impact. Well, I was wondering what are some existing practices of bridal practices that exist in the Sundarbans?

Upasona: OK, so uh as a practice, as a cultural practice, we don't practice bride price. We give dowry. So that is a kind of traditional rule. And we still give dowry to our daughters. But this particular point, this particular practice, has a negative impact. Somebody who is saying that I won't take any dowry to get married to your daughter and at the same time I will bear all the expenses of marriage. So, the parents are very happy and gladly, you know, let the girl marry. So, you see, if a girl is like growing up, she's educated, so you tend to think that as I'm economically getting poorer, how can I arrange dowry for my daughter? So that is a common perception. Maybe I have built some asset which I would have given to my daughter during the marriage, but that has been washed off in the last flood. So, I don't have any means to get my daughter married off with a good amount of dowry. So, in that case, somebody came to me and said, see, I'm very liberal. I don't want any dowry. I just want your daughter. And I will also take care of the expenses of the marriage. So it is a brilliant offer and the marriages are happening. So here again, climate change indirectly plays a major catalyst to this kind of marriages.

Reetika: Are marriages, which are like, you know, sources of trafficking and other things. Is that what you're trying to say?

Upasona: Yes, not all the marriages are, you know, source of trafficking, Yeah. but many of them are ended up in a, you know, human trafficking. OK, OK. So that that the thing.

Reetika: Right, right. You know, on that note, one of the things that I wanted to ask you was that when you spoke about dowry, what have you been hearing from the field, you know, in terms of over the years, see, like you pointed out earlier, like the last 20 years have had a huge impact on the livelihood opportunities. And, you know, the economic social insecurities have increased. How has dowry sort of changed, you know, has it sort of become, has it been negotiated differently or, you know, what are some of the ways in which these exchanges have been impacted?

Upasona: So, two twists are there. One is you can give in kind not in cash in kind. You can give a house or plot of land or plot of agricultural land, or maybe a motorcycle or motorbike. So, that is a very, you know, lucrative thing for a groom. So, this kind of thing and ornaments to the girl. So, we basically we are now you know focusing on kind not in cash. And at the same time, if the girl is educated to some extent at least to the secondary level, so here, the rate of dowry is bit lower because the girl will work and earn and take part in the household economy. So, if your girl is not that educated you have to give more dowry and your if your girl is more educated then the people will take less dowry, but they have to take part in the household economy. So there is a tendency, even before the climate change impacts, I mean, the increased frequency of climate change impacts, the Sundarbans peoples, they make their girls learn more as well, because they will get a good groom in the city. So, the mega city Kolkata is quite near to the Sundarbans, it is just 150 kilometers away. So, there is an impact of, you know, so-called city life. There is an aspiration of city life. So, if I am educated, if I cross my secondary education, if I pass my college, I would get a groom from a nearby town. And that aspiration and definitely the town groom will take less dowry because I will anyways earn and contribute to the household. So, dowry has changed its face, but it's still there.

Reetika: You know one thing that you are, uh, very clearly highlighting is the link between labour and livelihoods and the impact that it has on intimate everyday relationships as well. And one of the things that I wanted to now focus a bit on were the stakeholders involved. When we talk about these arrangements or you know when we're talking about even labour arrangements or marriage arrangements or say trafficking as well, who are some of the key stakeholders involved. Well, in that sense, you know, like, I mean, how do these things get fixed? And who are the people who are decision makers on the ground?

Upasona: I would say that you know for trafficking, there are hidden players that can come in any phase like it can be your relative, especially the distant relative, it can be your own family member who is influencing the marriage or the trafficking. And even if it is not trafficking, even for the marriage, the community itself takes the initiative to get the girl married off. So, basically it can be neighbours, it can be your dad's friends, or it can be your relatives. It can be anybody. At the same time, there are some players who are against this practice. They are also playing a crucial role. So first, definitely the government because they have a child anti-trafficking cell, who are actually enforcing the laws. The school teachers are also playing a very crucial role, and there are some NGOs who are the anti-trafficking NGOs. They are working really hard to, you know, stop these practices. But at the same time, I would say the most important player definitely or the stakeholders are the parents in may of the cases, I mean this is not particularly in Sundarbans, it is common everywhere. If the NGOs come, if the government, police come, the parents say that my girl is above 18. And there are, you know, many parents, even they do, you know, they make false birth certificates or false PDS [Public Distribution System] card to prove that the girl is above 18. So, I think the parents are the most crucial stakeholders. Because maybe they are in dire stress, of economic stress, or they are they are desperate to, you know, I mean, they sometimes they feel like, if we get our daughter married off, she can have a better life in in some other place which is not as vulnerable as the Sundarbans. Their own being, you know affected by cyclones or floods. So sometimes that is also in the parents’ mind and I mean, nobody to blame but the situation is very complex.

Reetika: No, absolutely. And I think that is one of the reasons, right? Like when we talk about this whole element of, you know, one, Uh. two things that you point out was just the idea around age itself where there are practical sort of challenges of defining age and our laws in some way are defined around that right. What are some of the challenges that you face with that? Can you speak a little bit more on like you spoke about like documentation? You know what are some of the ways in which that you think that these stakeholders are part of the problem as well?

Upasona: See I have couple of anecdote. I have talked to NGOs who work against trafficking. I recently met an NGO which is working on trafficking since the last 10 years. In the last 10 years, they rescued at least 19 to 20 girls, all were trafficked. But I mean, the major narrative of the NGOs working there or the government is like the parents need to understand. Though I haven't talked to any parent because that is a very hush-hush matter, you know, nobody will agree that their girl was below 18 years. We even conducted some FGDs [focus group discussions], we conducted some in-depth interviews, but nobody was you know… because they know they have done something against the law, they are fully aware of that, it's not like you know that they are saying that “yes, we did that. So what? We think it is right, we did that.” Everybody knows that they have done something wrong, every parent. So that's why they don't want to, you know, open up. But the NGOs are very vocal. Even they were like, yes, this family has done an underage marriage. But the argument that the parents are giving, that our girl was uh, you know above 18. We haven't done anything wrong. And you know that each, especially the girls who are aged like 16-17, it's very hard to you know, just by looking at their physique, the line between 16 and 18 is very blurred. You cannot just by seeing them, if a girl is healthy, you cannot say. So, here the advantages they are playing, especially the parents. And another problematic thing is that you know, by the next year, even if it is not trafficking, it is a simple marriage. By next year, the girl would be pregnant. So, the entire life course of a girl, she became malnourished because the food is scarce in the house. With all the micronutrient deficiencies like, you know, anaemia is very prevalent there. So, the girl is growing up, and as soon as she reaches the age of 15, she gets married, and by the age of 16 or 17 she should have a child, which is again a low birth weight baby, because the mother is undernourished. And that baby also carries out this same cycle. So, the entire life course, it's based on cumulative disadvantages. In terms of health, if we see it is a cumulative disadvantageous. But that perception, that understanding I can't say that the people are not ever fully aware about that. But it is a distress choice. They know what is right and what is wrong, what is good for their girl and what is not good. But it is they are in stress; their existence is at stake. So, they hardly have any choice.

Reetika: Yeah, absolutely. And I think this whole intergenerational passage of these vulnerabilities or these conditions is something which you bring about, I think is very, very crucial. I just have, like, two more questions in the conversation. One of the things I wanted to ask you was on the impacts of the pandemic, which continues to rage on what I've already the region is vulnerable, going through a lot of things. And what has COVID done now, you know, how have these things what is happening on the ground, essentially?

Upasona: OK, so yeah, this I should have mentioned it earlier also. The COVID situation, like in other parts of country, we the count that we count the gravity of the COVID situation in terms of death or you know morbidity. But here the problem was, in Sundarbans the problem was they, I mean, most of the people who had out-migrated, they came back, they stayed in the temporary medical camps and they were at home. So, that's not a problem. I mean, in terms of COVID disease, Sundarbans didn't have much impact. So, most of the areas are very remote areas. And at some point of time government, you know, closed the gateways to get into the Sundarbans. And in a way they did right because the health infrastructures are very poor in Sundarbans. So, it may not be possible to handle if there was a, you know, huge burden of disease. So by terms of disease, there was no problem. But the remittance, the people were earning the remittance, that was a huge loss. And you know, according to the anecdotes of some NGOs working there, marriages and, you know, trafficking have increased during the COVID. Because people don't have any other options and even during the, you know, strict lockdown, they had marriages. Thought I cannot say these are scientific data, it's with just anecdotes from the field. So, the NGOs I worked closely with, they said that, you know, the marriages had increased. So, some NGOs I know, they started counselling centres, they had to start counselling centres because schools were closed. So, another crucial point was schools were closed. So, the limited amount of counselling the parents or the girls were getting, that had also stopped. So, the NGOs had to start counselling centres, counselling camps just to make the parents understand. In one of the very vulnerable islands called Mousumi, they had to start counselling camps just to make them understand that they shouldn't drop out from school and don't get married, and just wait for the pandemic to be over and start their lives afresh. So that happened.

Reetika: Yeah. And I think one of the things that the pandemic also did, like you also pointed out, was sort of bring to the fore already existing vulnerabilities, and increase it manifold. That takes me to the final question, which was what are some community-driven solutions or what is a way forward? In some way, you know, because you spoke about state intervention, you spoke about the ways in which you know families sort of negotiate with the law and other things. But what are some community-driven solutions that you've been seeing on the ground and you think which need to be worked on in the near future?

Upasona: OK, so this question is very crucial to answer because many people ask me this question, but honestly, I don't have any answer because there is no straight line. If you say community-led interventions or community-led initiatives, is there any initiative which is community-led, I don't think so. All the interventions, all the initiatives, though very well meaning in the Sundarbans or in other vulnerable areas also, those are community-based. But very few of them are community-led. The community of Sundarbans, they are very busy just to you know, secure their survival. They don't have anything in their mind. So it is high-time to test their resilience. We just need to stop to test their resilience. And we need to think of long-term planning. It can be, you know, and as mentioned by many scientists, planned evacuation or another alternative skill building, or maybe some ecological restorations. We have to, you know, identify the loss and damage adaptation policies. We have to have to check what about the loss and damage adaptation policies there which will work or which will not. We need to think of long term beyond short-term disaster risk reductions. We have done enough about the disaster risk reduction. The region like Sundarbans they definitely require the disaster risk reduction plan but they need beyond that also. So, unless the policymakers, the policy interventions are towards that, it is very difficult to, you know, get into the root of the problem. People are very busy, people are simply busy to secure their survival. We have done enough. So personally I feel like, you know, community has done enough. So they need resources, they need support. Do whatever you have to do, but do something. I mean, we cannot just leave them like this. I'm not an expert to, you know, say that this is, this is the way out. This is a very complex situation and no single way out is, you know perfect. So if we talk about climate change transformations, we need many transformations. We need many adaptations. Not a single line. So if we if we think adaptations are transformation in silos, we would be failing again. We have to think multiple pathways of reducing their vulnerability and, you know, make them at least secure, their futures secure. So you know, when I started working in 2011 in Sundarbans, the people were not ready to leave the land. They say that it is the mother land. So, you know, the so so-called motherland sentiments were there. But in last 10 years they are they are so phobic. They want to just get out of this island. At least for their children. They are trying their best to, you know, make their children get out of this island. They don't want their children to be there. So that's their future aspiration and they know that their generation is finished, they can't do anything. Whatever they are, you know, gathering the assets for their children to stay out of Sundarbans. Even by marriage, even by education, even by whatever means, they just want their children to be out. So that is the situation. And I really don't know what is the solution.

Reetika: Yeah, you make very compelling points there. And yeah, I think it is a very complex problem at hand as you point out. Before we end the call, I just had one last question to just go back to something that you pointed out earlier. And I was wondering with you know, the location of Sundarbans being so crucial, right, in this whole conversation between like India and Bangladesh. Just in terms of the existing conversations around you know migration and refugee crisis and other things, what does climate vulnerability do to you know, this existing social political situation at hand and how does it affect the women and girls in particular?

Upasona: OK. See, I mean both the both the countries with the Sundarbans are facing the same problem, but the important point is that you know we know that there are migration, there are influx from Bangladesh part from Indian part. I mean it's both ways, it's not the single way, it's both way, and both the governments know that, we all know that. But the thing is that there are some treaties also between two governments regarding migration, regarding other political issues, especially the water issues. So, but the major thing I guess like there is no platform between the countries to you know learn from each others’ experiences. Like if I say that's, you know, Bangladesh has done quite a quite a lot of thing on the climate adaptation, especially in the vulnerable region like Sundarbans. So, India needs to learn that. And some other things. India has done. Bangladesh needs to land that. So unless we are, you know we are in a position to create a platform to learn by the countries and maybe from the failures like some interventions which have already been, you know, failed climate change interventions or climate sensitive interventions, which has failed in Bangladesh, Indian parties are repeating that now. I mean, there is no point repeating because the ecology, the people, the geography, the geo-morphology are same. So which has failed there, it is going to fail here also. So, that understanding needs to be built. And we may like to think, I mean it is a future call or I'm working towards that also. To think Sundarbans beyond this political boundary, to think of the Sundarbans as an unified region. And try to find the solutions irrespective of whether it is a part of India or the Sundarbans part of Bangladesh,

Reetika: I think again, thank you so much. I mean, I've learned a lot in the last hour that we have been conversing.

Upasona: So my pleasure, complete with my pleasure. Thank you, Reetika.

Reetika: The Climate Brides podcast is supported by the University of Cambridge Public Engagement Starter Fund 2021. If you want to learn more about today’s topic, head over to our website, where we will have full transcripts of the episode, a specially curated reading list, climate models and infographics. Until then, subscribe now wherever you get your podcasts. Follow the Climate Brides page on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook to stay tuned, and stay updated.

Episode Credits:

Researcher and Host: Reetika Revathy Subramanian

Music and Sound Producer: Siddharth Nagarajan

Illustrator: Maitri Dore